Pushing a New Paradigm in Toxicology Testing

New research from the Physicians Committee offers a way forward for elevating accurate, nonanimal toxicological testing methods.

Researchers with the Physicians Committee have been working hard to support the development of nonanimal test methods for the study of a serious occupational hazard. While the traditional animal-testing toxicology paradigm was developed in the early 1900s, scientists are now beginning to appreciate the many limitations of animal tests as well as embrace alternative perspectives—and methods—within the field of toxicology. For better or worse (we think worse), animal test methods have long been used to approximate human health hazards, but for chemical respiratory allergies, animal methods can’t even begin to approximate the physiological process that occurs in humans. Science’s overreliance on the “endpoint” paradigm in toxicology has prevented us from being able to adequately protect workers from a major occupational hazard prevalent in many industries, like woodworking, adhesives and paints, and cosmetic dyes.

Due to complex species differences in both the respiratory tract and the immune system of test animals and humans, traditional toxicologists have not been able observe this endpoint in test animals. One reason for this is that chemicals interact with different portions of the respiratory tract depending on the physics of inhalation—rats and mice, along with guinea pigs and rabbits, have radically different respiratory tracts, in which airflow is mostly horizontal, while human respiration relies primarily on vertical airflow. This causes chemicals to accumulate in entirely different parts of the respiratory tract in animals. And the situation for respiratory allergy is further compounded by the myriad of human-specific immune processes involved in chemical allergy responses.

Fortunately, the next generation of toxicologists is looking at chemical hazards differently and collaborating with clinicians and chemists to understand how hazardous chemicals act in the human body to cause adverse outcomes like allergy, also known as sensitization. A few years ago, a collaboration led by the Physicians Committee outlined the steps in the Adverse Outcome Pathway (AOP) of chemical respiratory sensitization as a first step toward establishing what we already know, and what we have yet to learn, to evaluate test methods.

We need to develop reliable test methods in order to accurately identify which chemicals warrant extra protections, like personal protective equipment and environmental exposure limits for workers and consumers. But before we can answer whether test methods identify respiratory sensitizers, we have to have high confidence in a defined reference set of chemical sensitizers. It’s a catch-22: We can’t know what methods work because we don’t have high confidence in a reference set, and we can’t use any methods in development to define a reference set because they haven’t been evaluated. And, although skin sensitizers are better understood because of clinical testing, respiratory sensitizers are too toxic to test on volunteers.

Luckily, at the Physicians Committee, we’re always up for a challenge when it comes to establishing and advancing human-relevant approaches, so we organized a diverse team of experts including everyone from computational chemists, chemical biologists, pathophysiologists, to respiratory therapists to work together to establish a reference list of chemicals shown to cause respiratory sensitization in humans. And through this collaboration, that’s precisely what we did.

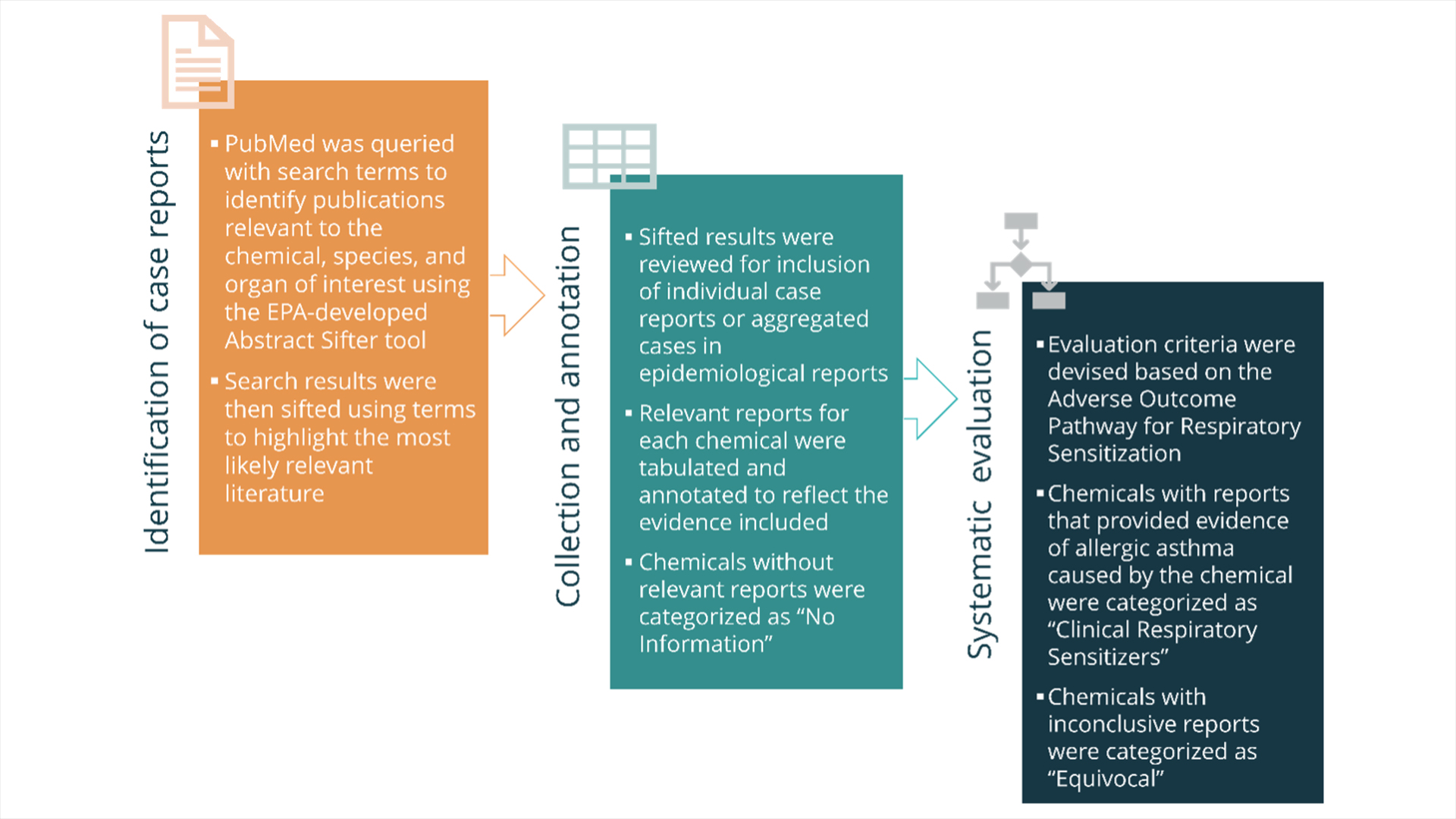

Working from a list of chemicals suspected to have respiratory sensitization potential based on their chemical structure, instead of “screening” each one through a lab test, we mined the literature for the gold standard of human health—clinical data. While we don’t test respiratory sensitizers in people proactively, monitoring environmental exposures to reactive chemicals in the workplace has been an essential method in many areas of occupational health and toxicology. When a patient shows up with symptoms of chemical respiratory sensitization, those incidents are sometimes published in occupational health literature as case reports. And included in those reports are exposure histories, as well as data from inhalation and allergy testing.

Through a diligent effort to catalog and read through all the case reports we could find for each chemical, and with attention to what we know about respiratory sensitization through the AOP, we were able to identify twenty-eight different chemicals that have been documented as causing respiratory sensitization in humans. We can now move forward with evaluating the many different computational and in vitro test methods in development and forge a path toward protecting human health with the first test methods validated based on a chemical reference set driven by clinical data. The Physicians Committee will continue to work with test method developers and regulators to establish a testing strategy to identify additional chemical respiratory sensitizers based solely on nonanimal test methods, but for now, we’re off to a tremendous start.